Perspectives: Murder in the Clavist Autonomous Zone

What follows is a synthesis of thoughts and discussion related to Murder in the Clavist Autonomous Zone by Rich Larson.

These largely come from a series of discussion sessions at RightsCon 2025 in Taipei, Taiwan. They are intended as fodder, inspiration, and incitement for creators to dig deeper on surveillance technologies and consider intersections in their own forthcoming works.

Should the crime or tragedy of one be used to permanently take away the rights of many?

This is, at the core, why so many resources are going into this toolkit—because the power of one humanizing or gut wrenching story can shift the tide of a cultural movement. Or, it can be held up as an example of why the rights of many should be taken away.

The movement for kids’ online safety in the US is rife with individual stories of kids who suffered extraordinary harm through the Internet, examples that to many seem unassailable even as laws that won’t stop what happened to those kids are passed in their names. In practice, these laws would censor the speech of activist movements and deplatform marginalized communities en masse while increasing surveillance of all people online. Yet malicious actors manipulate grieving parents and those sympathetic to them into fighting for the tools of oppression and authoritarianism.

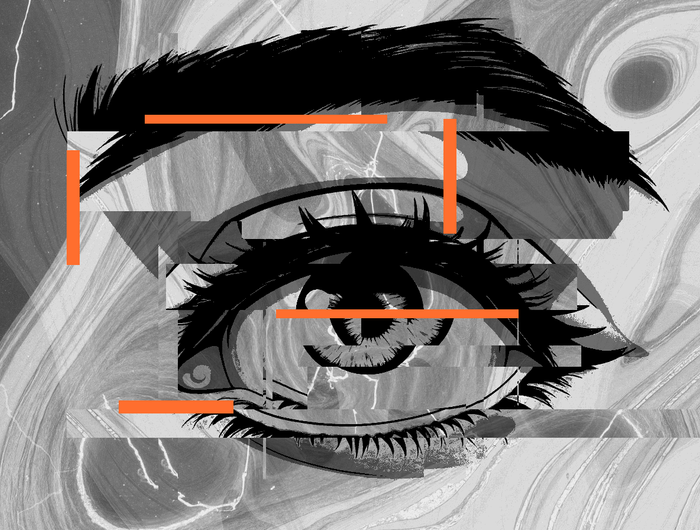

In this story, murder becomes an excuse for surveillance. It’s a classic tale of crime-drama exceptionalism, in a way—but flipped to the other perspective, of the community that’s being invaded. The stark truth that this story so aptly illustrates is that no interaction with surveillance policing is only about the surface-level reason for the police incursion. For example, police often surveil protests with military technologies with the excuse of peacekeeping, when the intensive surveillance is really about data collection on a group that’s participating in the protest.

A RightsCon participant who works with undocumented communities in the US recognized many parallels here in their own work—that generally, undocumented communities have a system very similar to the one in the story for interacting with police. They only talk to police to prevent them from digging deeper or penetrating further or causing more harm in the undocumented community. There are established lines of cooperation for these procedures that offer the minimum of what’s required to keep the police as distant from the community as possible.

More:

Grappling with individual and community accountability

"Some of the tech description washed over me but the intimate moments of grappling with one's body and accountability relationality stood out a lot more.” — RightsCon Participant

This story raises a great question: what does accountability and transformative justice look like amid a surveillance state? This is a question that many of us who work on these issues every day grapple with.

We find that it’s often a lot easier to imagine and even live out some level of liberation in a smaller community—but that such communities can often become insular, even cult-like, and that their approaches to honesty around violence and harm, as well as around trust, are often less than perfect. Or, they descend into witch trials, flippant cancel culture, or trial by mob.

Many of us have been trained by our culture and neighborhood watch apps to bring our own policing gaze as a way of defending our own communities with individual surveillance. We honestly all need more narratives of alternatives to this sort of surveillance mentality, and more interrogations and ways of thinking about the realities and systems of trust that we might evolve toward.

“As a security professional, I would like to see a world between trust-verify and a mechanism to revoke trust. If you had mechanisms that were foolproof it would provide a confidence and a resilience that people don’t currently have” - RightsCon Participant

A community that invests in itself to the exclusion of so-called “progress”

Urgency in technology is a weapon against free thought. In a similar way to our discussions of how authorities displace accountability by blaming the computer, surveillance hawks and hawkers rely on the urgency of threats and “latest and greatest” marketing cycles to scare or seduce us all into adopting tech before we understand it.

In this story, slowness is a part of resisting the frenetic surveillance culture outside the clave—a familiar sense of tech "progressing" and rest being antithetical to modern safety and cultural relevance. It is meaningful and symbolic to an activist community constantly fighting burnout that the main character chooses to heal her bullet wound slowly. It would be more convenient to leave the clave and have her wound instantly healed—but it is illustrative of her cultural anti-surveillance values that she chooses what is less convenient. To heal slowly is to rest, recover, take the time to think and process the injury and the circumstances around it. This gives her more autonomy in her own mind about what happened, versus what might happen to someone else who had been shot outside the clave—authorities count on the fact that people without time to think will just comply.

This is one of the most important places where people subject to surveillance tech (i.e., all of us) are the fish that is asking “What is water?” Urgency feeds the normalization of a particularly reductive and incomplete state of safety and security—one defined by corporations and governments and careless pop culture. That least-common-denominator standard is what needs to be broken apart and exploded, as Larson does here. By seeing different ways of being, we can redefine first what safety and security actually mean and challenge our defaults. Rejecting that feeling of always being behind, is a front of resistance against tech changing your brain, your work, your life, always on its terms.

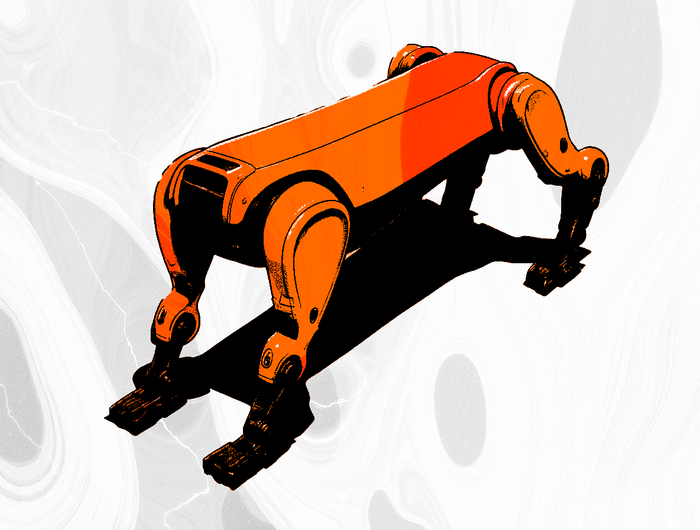

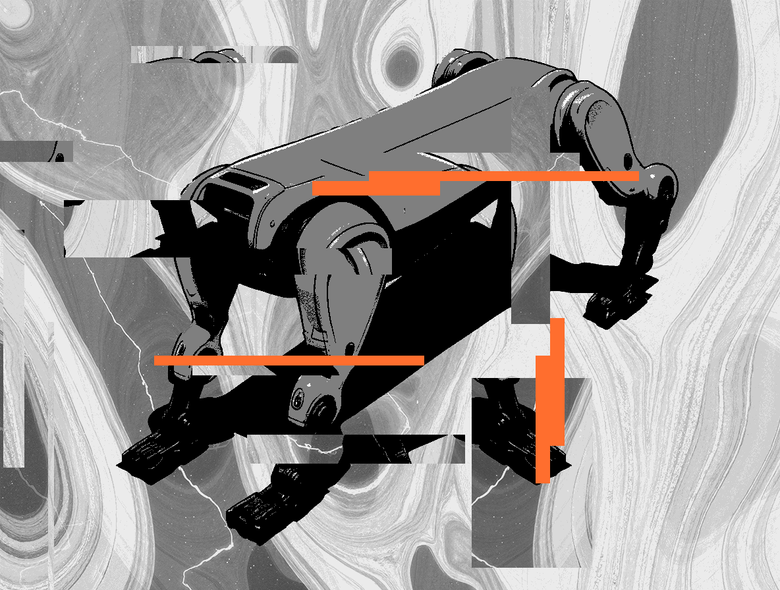

We can trace these threads in the remarkable fact that the community immediately knew who had committed the murder, in contrast to the robot dog who interviews many others. The dog’s interference is entirely redundant to what the community had done itself. And how did the community know? Because they have invested time in knowing and witnessing each other.

A community that knows itself well and is connected can potentially solve issues better and faster than a community that is disconnected and surveilled. This seems to be what the state hates in this story—how powerful they are without surveillance, and how much more joy and diversity of experience is available to them, too, without the state’s interference. In this story, it’s clear that not only the dog but the state is exterior to the community, and does not belong.

More:

-

Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto by Tricia Hersey: https://app.thestorygraph.com/books/6b770a6b-f640-4590-9578-b1287ad236ea

What does “care” mean?

The dog critiques lack of surveillance in the clave as a lack of community care. The dog’s propaganda comes from a paternalistic and harmful view of care, similar to how an abusive or enmeshed parent might characterize invasive surveillance of their adult child as care.

Surveillance as an act of caring is old school propaganda. Many of our first introductions to the concept of surveillance is with a parent invading a diary or lurking on a phone call. So, proponents present state or corporate surveillance as only an extension of such care, as in Orwell’s Big Brother. It’s a common trope for youth to demand privacy as a refrain, and for a parent to grant or deny it based on whether the child has earned their respect. The analogy falls apart when you consider whether corporations and governments are capable of granting respect—or if people are capable of earning it from them. Even in the parent-child power differential, it’s broadly accepted that a relationship of invasive surveillance should not continue once the child’s brain is fully developed.

“Santa Claus is mainstreaming surveillance for children!” - RightsCon Participant

The disrespectful power differential in this story peaks when the dog defends its robotic carapace at the risk of the main character’s life. While a machine can easily be repaired after it is stabbed with a knife, a human cannot be brought back from a deadly bullet ricochet. The clave community already knows never to mess with the dog, and their ingrained fear is further justified when the machine shows that the state values avoiding the inconvenience of repairing a robot over multiple human lives.

More:

-

1984 by George Orwell: https://app.thestorygraph.com/books/6ff3f487-8d37-4ac5-8190-6622d6562639

-

https://medium.com/@walt.t.downing/paw-patrol-is-a-republican-dystopia-f178161fce54

Post-surveillance narratives

This is the only story in our toolkit that presents a post-surveillance narrative and many readers appreciated it for that reason alone. Having creative people digging into how a community navigates away from surveillance, through transitional change and the messy middle is extremely valuable. This is hard stuff to grapple with.

Being a member of the clave is a very strong identity amongst, it seems, all members of the autonomous zone. Their pastimes include art, partying, working with their hands, and hanging out in a cool lemon garden—all efforts at expression and connection that are not intermediated by technology. They also have a warring curiosity and aversion to the intoxicating elements outside the clave’s walls, a strong sense of us and them, and the need for each community member to see both worlds and make a conscious choice of which they belong in.

To accomplish that shared vision, there is a religious quality to how the community maintains itself and its dimmers. This raised a variety of good questions:

-

How to implement, sustain, and depict post-surveillance community values?

-

What alternatives to religion are there for decentralized but effective community authority or governance?

-

Must there be shared beliefs to live without surveillance and subvert dominant narratives?

-

Does a community need to be rather homogenous, as this one is, to stay united?

-

Could the value of privacy be a connecting belief across a wide range of different thought systems?

-

Would diversity of thought or lived experience make what many of us perceive as a culty community stronger and more resilient?

"Imagining a different society is actually pretty hard" - RightsCon Participant

While this story sparked some of our most lively discussions around a particular technology—the robot dog—the RightsCon community also had a lot of curiosity about what wasn’t on the page. Recognizing that with storytelling you only have a limited number of words to frame the different dynamics and shed light on the world, there’s a lot more about this sort of world and community that an author could explore, like:

-

There is no answer for how this community would want to heal or do restorative justice. We’re hungry for a community’s alternatives to the robot dog and the implied carceral state outside the clave.

-

One participant wondered what this story had at the heart of it—the goal of presenting an alternative or of critiquing one technology.

-

How can you be autonomous if you can't resist law enforcement? Ultimately, the clave wasn’t able to avoid law enforcement’s intrusion or pursue justice in a way they would choose—does this make their ‘autonomous zone’ more of a grey area? What are the juicy tensions there?

-

The clave talks about who committed the murder as a whisper network vs. any sort of collective or community governance. Wouldn't the whole point be the community trying to do things together vs. one individual hero getting a confession?

-

"Credit to movement work"—post-surveillance stories that focus on investigating how a community was formed and its social structure are very welcome. An autonomous zone implies a large degree of divestment from state infrastructure, and how that might be done is fascinating.

-

There’s room for more reflections on discipline and rigor in communities that resist police surveillance technologies.

-

Stories that explore these dynamics, but in a mass-market format as opposed to one that appeals mostly to readers of the science fiction genre.

Love that this story chooses…

-

TO reclaim drug use/mind expansion & anti-surveillance/liberation together. Often these days with things like venture capital backed mushroom trip apps collecting and selling data on users, so-called “mind expansion” ends up looping back to be about control once more.

-

TO weaponize cute. Cute can be used by both sides, but in this case it is so well done and sinister—nobody in the clave believes the dog is a friend.

-

TO NOT capitulate to catastrophizing for surveillance to protect from unrealistic/extreme threats. So often tragedy is used to justify massive surveillance expenditures.

-

TO take on the cultural normalization of robot dogs head on. These violent and problematic machines are getting integrated into culture quickly, as with Janelle Monae posing with a robot dog or exhibitions where artists use robot dogs to paint. Robot dogs are death machines and cool-washing them needs to be rejected.

-

TO make room for the importance of privacy for experimentation and self-discovery. In the clave, it’s clear that time and human interaction are allowed to change community perception—versus the permanence of a surveilled record where what you said 10 years ago can be used to upend your life.

-

TO let terrible people be victims too. The murderer’s ultimate choice to defend the community shows that morally terrible people can also resist and be victims of surveillance. The story makes room for him as a victim of the seductive surveillance ubiquity outside the clave that disconnected him from the world and left him empty. His return and hope for a relationship with his son was an attempt to find his humanity again after being preyed on and manipulated for so many years by surveillance tech.